Standard 4: Assessment

Timely education assessments of the emergency situation are holistic, transparent, and participatory.

On this page

1. Rapid needs assessment: Conduct a rapid needs assessment as soon as possible, with consideration for the security and safety of the assessment team and the people affected.

See Guidance Notes:

2. Comprehensive needs assessment: Conduct a comprehensive assessment of education needs and resources for the different levels and types of education.

See Guidance Notes:

3. Cash and voucher assistance: Conduct a needs assessment to collect information on the economic barriers to accessing education.

See Guidance Notes:

4. Assessment teams: Form an assessment team with balanced representation and ensure that team members receive proper training before they collect data.

See Guidance Notes:

5. Disaggregated data: Collect disaggregated data that identify the perceived purpose and relevance of education for the local community, barriers to education access, and priority education needs and activities.

See Guidance Notes:

6. Data responsibility: Collect, store, share, analyze, and use data safely, ethically, and effectively.

See Guidance Notes:

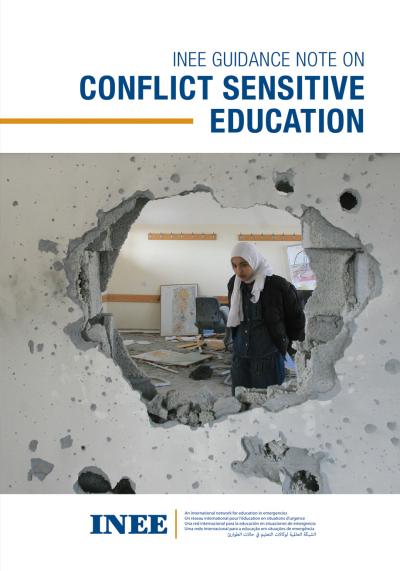

7. Context analysis: Conduct a context analysis to ensure that the EiE response is appropriate, relevant, and sensitive to the potential for risks and conflict.

See Guidance Notes:

8. Community resilience: Identify local capacities, resources, and strategies for education, crisis mitigation, preparedness, and recovery before and during the emergency.

See Guidance Notes:

9. Participation in assessments: Ensure that representatives of the people affected and the education authorities participate in the design and implementation of data collection.

See Guidance Notes:

10. Collaboration within the education sector and with other sectors: An inter-agency coordination mechanism coordinates education assessments with those by other sectors and actors.

See Guidance Notes:

11. Assessment findings: Share assessment findings promptly with a wide range of stakeholders, especially the people affected by the crisis.

See Guidance Notes:

Data collection and needs assessments should be kept to a minimum in the early stages of a response. When a crisis arises, data should be collected through a multi-sectoral rapid needs assessment. This should be done as soon as it is safe for the assessment team and the people affected. Multi-sectoral assessments minimize cost, increase efficiency, and reduce the burden on the people affected. The goal of a multi-sectoral assessment should be to create a first snapshot of what the people affected need and understand their priorities. Stakeholders such as the national government, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), UNHCR, or United Nations Development Programme have specific mandates to do this work and thus should lead or coordinate multi-sectoral assessments.

It is essential that education is represented in multi-sectoral assessments. In countries with an active, formal rapid response mechanism, education questions should be integrated into that mechanism’s assessment question bank. Humanitarian actors can use the rapid response question bank in the GEC’s Strengthening Rapid Education Response Toolkit to contextualize education questions in a rapid response mechanism assessment. Assessment and analysis should continue in the later stages of a response, and should include girls, children with disabilities, and other potentially vulnerable children and young people. Humanitarian actors can use an environment assessment tool, such as the NEAT+, to ensure that a response is sustainable. This kind of tool will help actors identify environmental concerns before they design longer-term emergency or recovery interventions.

After completing the rapid needs assessment, EiE stakeholders should conduct a comprehensive inter-agency assessment of the education sector, such as a joint education needs assessment (JENA). National education authorities and the education coordination mechanism should coordinate and manage joint assessments. A rapid JENA may take place up to a month after the onset of a crisis, followed by a more detailed JENA later on. A JENA aims to determine the impact of the emergency on learners, communities, and the education system. It should collect information on education capacities, resources, vulnerabilities, and gaps and challenges to the right to education for all, across all levels and types of education. A joint inter-agency needs assessment is the highest standard for an education assessment, but the type, depth, and scope of an assessment will depend on contextual factors, such as the resources available, capacity, and decision-making time frame. Emergencies are complex, and the needs of the people affected change over time. After the initial assessment, EiE stakeholders should regularly update the data through monitoring and evaluation to determine achievements, limits, and unmet needs. The findings for each phase of a crisis should guide the design and focus of later assessments.

Assessments should make the most of existing information sources. This is known as secondary data, which can include published research, government reports, online material, and data that has already been analyzed for other purposes. Assessment teams should analyze the secondary data before collecting primary data. The primary data collection should be limited to what is needed to fill urgent knowledge gaps and guide critical decisions. If access to some secondary data is restricted, other sectors or pre-crisis databases can provide useful secondary data. Pre-crisis data provides a measure against which to compare the emergency situation. Local leaders and community networks can help assessment teams reach members of the community to collect primary data. Stakeholders conducting the assessment should respect local and indigenous communities and knowledge systems and include them in the assessments.

Preparedness for assessments is usually led by the inter-agency coordination mechanism in cooperation with education authorities. Education authorities and the inter-agency coordination mechanism should standardize data collection tools in country so it is possible to coordinate projects and minimize the demand on the people sharing information. Relevant stakeholders should aim to develop and agree on the assessment tools they will use during preparedness planning. Training people to use these tools is also an important part of preparedness and contingency planning. The tools should include space to add information the local respondents consider important, which will enable them to express their needs fully. Collection tools should be developed using the method and software best suited to the situation. This may be a paper-based collection tool or a mobile/electronic tool. The time frame, budget, and capacity of the assessment team are also important to consider. (For more guidance and resources on planning, coordinating, and conducting needs assessments, see EiE Needs Assessment Package.)

Inter-agency coordination mechanisms should assess education needs in an integrated way, from both the demand-side and supply-side perspectives. To determine whether CVA is an appropriate response modality, the assessments should collect specific information on the economic barriers to education.

Multi-sectoral assessments and comprehensive education assessments should include cash-related questions, where the situation allows. This will help to determine how education costs and negative coping mechanisms might be addressed with CVA. Information on CVA can help stakeholders identify the following:

- The education services available

- The benefits of using CVA instead of or in addition to in-kind and direct service delivery

- The delivery modalities that the people affected prefer, such as CVA, in-kind, or direct service delivery

- The physical access those affected have to markets

Additional assessments are needed to determine if CVA is feasible in a particular area. If a non-education CVA feasibility assessment is planned, education stakeholders should advocate including education-related questions. If this is not possible, they should work with the cash working group or other sectors (e.g., child protection, food security, livelihoods) and organizations with strong CVA expertise to adapt cash feasibility assessment tools to collect information on CVA in the education sector. Feasibility assessments of both types can help stakeholders identify the following:

- The capacity and functioning of markets for education-related goods and services, such as uniforms, school materials, and transportation

- The protection and operational risks associated with CVA

- The options available to transfer money to the people affected

When forming an assessment team, it is important to consider the team members’ profiles. The teams should include people from the affected community, as they will bring their knowledge of the local context and understand how to operate effectively in that context. This also will help with the data collection because members of the community have connections to local networks. The teams should have a balance of genders to reflect the experiences, needs, concerns, and capacities of learners, teachers and other education personnel, and parents and caregivers of all genders. An inter-agency assessment team should have a balanced representation of languages and organizational affiliations, and national and international staff members. Systems should be in place to counter any explicit or implicit bias that might affect the way assessments are planned and conducted, and the way information is analyzed.

Assessment team members should receive proper training before they collect data. The training should cover the goal of the assessment, the methodology and tools, and the code of conduct. It should also teach the team how to get informed consent and to address concerns about protection. This includes their responsibilities in terms of child safeguarding and protection from sexual exploitation and abuse and gender-based violence. If some respondents will be children, the training should cover child safeguarding and child-friendly skills to ensure that the children’s participation is safe and meaningful (see the EiE Glossary for a definition of child-friendly) (for more guidance, see EiE Needs Assessment Package; Minimum Standards for Child Protection).

Teams should collect disaggregated data to guide the education response and assess any ongoing risk. Education stakeholders should design assessment tools to collect and analyze relevant information on different social groups, including their vulnerabilities, risks, and the effect the crisis has on education. Disaggregated data is important in understanding how different marginalized groups are affected by the crisis. The data should be disaggregated by sex, age, and disability status at a minimum, but can also include language, location, displacement or international protection status, ethnicity, and more. Teams also should collect disaggregated data related to other sectors that are linked to education, such as child protection, MHPSS, ECD, WASH, health, and nutrition. They should use secondary data sources as much as possible to collect this information (for more guidance, see INEE Guidance Note on Gender; INEE Guidance Note on Psychosocial Support; INEE Guidance Note on Teacher Wellbeing in Emergency Settings).

The varying nature of crises can make the data on vulnerable populations or on certain characteristics quite sensitive. This information can include religious or ethnic origins, language, political opinions, religious beliefs, physical or mental health conditions, and sexual orientation. Teams should take extra care when collecting potentially sensitive information.

The basic principles of respect and non-discrimination should be the foundation of any assessment. It is important to handle the data lifecycle—which includes collecting, storing, analyzing, sharing, and using data—safely, ethically, and effectively. All stakeholders who work with and manage humanitarian data should adhere to the following principles:

- Do no harm: Collecting information can put people at risk. Their information may be sensitive, and even just participating can put them at risk. Team members must ensure that personal information is protected in line with accepted frameworks. This may fall under national and regional data protection laws or organizational data protection policies. “Do no harm” also includes addressing any ongoing or observed protection issues and following child safeguarding protocols. If there is concern that children’s participation might cause them harm, team members should consult child protection actors

- Informed consent or assent: Those collecting information must protect participants and inform them of the following:

- Why they are collecting the data

- That they have the right not to participate

- That they can stop at any time without consequences

- That they have the right to confidentiality and anonymity

Parents and caregivers should give consent for their children to participate. The children should also be asked if they want to participate.

- Purpose driven: Data should be collected to strengthen the education response and collected only if there is a clear reason. Doing otherwise could create unnecessary risk and waste resources.

- Confidentiality: It is essential to keep participants’ data confidential throughout the data cycle. Stakeholders should take all necessary steps and safeguards to avoid violating confidentiality. Whenever feasible, personal data should go through an anonymization process.

- Transparency and accountability: Stakeholders should make the following clear to participants:

- What data they are collecting

- How they will keep it confidential

- How they will use it

- Whom they may share it with and how they will share it

- How they will keep it safe

- How individuals can ask for their personal data to be removed

(For more guidance, see IASC Operational Guidance on Data Responsibility in Humanitarian Action; Minimum Standards for Child Protection, Standard 18.)

Data analyses should clearly identify the following:

- Indicators

- Data sources

- Collection methods

- Data collectors

- Data analysis procedures

Where data collectors face security risks, the analysis should refer to the types of organizations involved in the data collection and not the names of the data collectors. The collectors should note any limitations of the data collection or analysis that could affect the reliability of the findings or how useful they may be in other situations. If the data shows that certain groups or issues are not included in programs and monitoring systems, the collectors should make a note of that.

To reduce bias and strengthen validity, stakeholders should collect data using several sources and then compare them. Sources can include classroom observations, focus group discussions, community group discussions, key informant interviews, and household surveys. Before drawing conclusions, the team members should consult with the most affected groups, including children and young people of all genders and persons with disabilities. To prevent the education response from reflecting the perceptions and priorities of people external to the context, local perceptions and knowledge should be central to the analysis.

Context analysis is a key step in the assessment process and usually part of a multi-sectoral assessment. It complements other assessment activities. Analysis of the context, including disaster risk and conflict analysis, can ensure that an education response is appropriate, relevant, and sensitive to the potential for conflict and disaster. Education stakeholders should consider the medium- and long-term implications of an intervention, including learners’ ability to integrate into formal programs, to complete certified non-formal programs, or to re-enter the education system in their country of origin. In refugee situations, the context analysis should include information on the education systems in the country of origin and the host country. It should document the differences and similarities in the curriculum, language, requirements, and structure of the two systems, at what levels certification exams are given, and trends in enrollment and completion in each country, disaggregated by age, sex, disability, and education level. The analysis should look at how these factors could affect refugees’ access to education, and at the legal framework that governs access to the national education systems or refugees’ access to education.

Risk analysis should consider all aspects of the context that may affect the health, security, and safety of learners, especially children and young people. This will help to make education a protective measure rather than a risk factor. A risk analysis assesses all hazards and risks to education, which may include the following:

- Insecurity, poor governance, and corruption

- Biological and health hazards, such as pandemics, communicable diseases, and air pollution

- Natural and climate change-induced hazards, such as earthquakes, floods, and wildfires

- Technological hazards, such as a toxic gas release or chemical spill

- Conflict and violence

- Risks related to gender, age, race, disability, ethnic background, and other relevant factors

A risk analysis report proposes strategies for managing the risks created by natural and human-made hazards, including conflict. These strategies can include prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response, reconstruction, and rehabilitation. For example, the risk analysis report may note that schools and other learning environments should have contingency and security plans to prevent, reduce, and respond to emergencies. It also could suggest that schools and other learning environments prepare a risk map that shows potential threats and highlights what may affect learners’ vulnerability and resilience. A useful starting point is the safe schools context analysis, as described in the Comprehensive School Safety Framework. This can help education stakeholders identify strengths and weaknesses, opportunities and threats, and guide national or sub-national strategic planning for school safety.

Conflict analysis assesses the presence or risk of violent conflict to prevent education interventions from increasing inequalities or worsening a conflict. This is necessary in both conflict and disaster situations. Conflict analysis should ask the following questions:

- Who is directly or indirectly involved in a conflict?

- Who is being affected by a conflict or is at risk of being affected?

- What has caused the actual or potential conflict?

- How do actors interact and what are the dynamics, including education stakeholders?

Research organizations often conduct conflict analyses for a region or country, which education actors should review from an education perspective. If no such analysis is available or applicable, education stakeholders can carry one out by holding a workshop in the affected area, or through a desk study. Education stakeholders should advocate for the right agencies to do a comprehensive conflict analysis that includes education-specific information, and to share their findings with all interested parties.

Education actors should complement the context analysis with an assessment of context-specific education capacities, resources, and strategies, including community resilience and coping efforts. The assessment should include digital literacy and technological infrastructure related to distance education, such as internet access and connectivity. If possible, education stakeholders should use preparedness and mitigation activities both before and after an emergency to assess and strengthen community knowledge, skills, and capacities for disaster mitigation, preparedness, and recovery. Local and indigenous knowledge systems should be included in the context analysis and assessment efforts. These unique ways of knowing can create a foundation for locally appropriate, sustainable development and help to guide community-based DRR and resilience strategies.

Education authorities and representatives of people who are affected by a crisis should participate in the design and implementation of assessments. When possible, EiE actors should encourage and support children’s and young people’s participation by conducting peer assessments, school risk mapping, etc. Their involvement should be contingent on the situation being safe and secure.

When conducting assessments, it is important to communicate in all languages used in the community, including sign language and braille, where applicable. Qualified translators and interpreters should facilitate communication.

To make assessments as comprehensive and useful as possible, it is important that education stakeholders collaborate within the education sector and with other sectors. To avoid duplication, they should conduct harmonized or joint assessments and coordinate field visits with other emergency response providers through the inter-agency coordination mechanism. This will prevent the inefficient use of resources and over-assessment of certain people or issues. Coordinated assessments encourage humanitarian stakeholders to share information and ensure that all affected groups are accounted for. This improves accountability and results in stronger evidence of the impact of an emergency and a more coherent response.

The education sector should work with other sectors to guide the education response to threats and risks and to determine what services are available. This may include coordination with the following:

- The child protection sector to conduct joint assessments and learn about the risks facing children who are accessing education and those who are not. Risks include gender-based violence, children who are unaccompanied or separated from their caregivers, harmful traditional practices, barriers to education, and a lack of social and MHPSS services (for more guidance, see Minimum Standards for Child Protection, Standard 23; Supporting Integrated Child Protection and Education Programming)

- The health sector to get epidemiology and other health data and information about the threat of health emergencies and to learn what basic health services are available, including services for sexual and reproductive health, for rehabilitation or early intervention for children with disabilities, and for HIV prevention, treatment, care, and support

- The nutrition sector to learn about school-based, community-based, and other nutrition services

- The WASH sector to make sure there is a reliable water supply and appropriate sanitation in the learning environment (for more guidance, see Sphere Handbook)

- The cash working group or food security sector to advocate for including education-related costs in the minimum expenditure baskets, to align CVA modalities, or to share information on payment mechanism options

- The shelter and camp management sectors to coordinate finding safe and appropriate locations for learning; building, rebuilding, and accessing learning and recreation spaces; and providing non-food items for the learning environment (for more guidance, see Minimum Standards for Camp Management)

- The logistics sector to organize the procurement and delivery of books and other supplies

- The ECD sector, which is often cross-cutting and embedded within existing sectoral interventions and may or may not have a coordination mechanism at the national or subnational levels. It is important to collect information on ECD efforts in education and other sectors during assessments to understand young learners’ and caregivers’ needs and determine who will lead overall ECD coordination across and/or within sectors.

Indicators

| INEE Domain | INEE Standard | Indicator/Program Requirements | Clarification | Numerator | Denominator | Target | Disaggregation | Source of Indicator | Source of Data | Available Tool | Crisis Phase | |

| Foundational Standards | Community Participation | Participation (FDN/Community Participation Std 1) Community members participate actively, transparently, and without discrimination in analysis, planning, design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of education responses. |

1.1 Percentage of parents actively participating in the conception and implementation of education in emergencies services | Number of parents consulted | Number of parents | To be defined by program | Gender | Based on OCHA Indicator Registry | Program documentation | No tool required; INEE MS and indicator definitions sufficient | All stages | |

| 1.2 Percentage of parents satisfied with the quality and appropriateness of response at the end of the project | Number of parents satisfied with the quality and appropriateness of response at the end of the project | Number of parents | 100% | NA | Based on OCHA Indicator Registry | Program documentation | Tool required | All stages | ||||

| Resources (FDN/Community Participation Std 2) Community resources are identified, mobilized and used to implement age-appropriate learning opportunities. |

1.3 Analysis of opportunity to use local resources is carried out and acted on | Scale 1-5 (1 = low, 5 = high) | 5 | NA | New | Program/procurement documentation | Tool required | All stages | ||||

| Coordination | Coordination (FDN/Coordination Std 1) Coordination mechanisms for education are in place to support stakeholders working to ensure access to and continuity of quality education. |

1.4 Percentage of regular relevant coordination mechanism (i.e., Education Cluster, EiEWG, LEGs) meetings attended by program team | Number of regular relevant coordination mechanism (i.e.; Education Cluster, EiE Working Group (WG), Local Education Group (LEG) meetings attended by program team | Number of regular relevant coordination mechanism (i.e. Education Cluster, EiEWG, LEGs) meetings held during organizational presence | 100% | NA | New | Meeting records | No tool required; INEE MS and indicator definitions sufficient | All stages | ||

| Analysis | Assessment (FDN/Analysis Std 1) Timely education assessments of the emergency situation are conducted in a holistic, transparent, and participatory manner. |

1.5 Percentage of education needs assessments, carried out by the relevant coordinating body the program has participated in | These include initial rapid and ongoing/rolling assessments | Number of assessments organization contributed to | Number of possible assessments organization could have contributed to | 100% | NA | New | Assessment records | No tool required; INEE MS and indicator definitions sufficient | All stages | |

| Response Strategies (FDN/Analysis Std 2) Inclusive education response strategies include a clear description of the context, barriers to the right to education, and strategies to overcome those barriers. |

1.6 Strength of analysis of context, of barriers to the right to education, and of strategies to overcome those barriers | Scale 1-5 (1 = low, 5 = high) | 5 | NA | New | Program documentation | Tool required | All stages | ||||

| Monitoring (FDN/Analysis Std 3) Regular monitoring of education response activities and the evolving learning needs of the affected population is carried out. |

1.7 Percentage of education needs assessments carried out in defined time period | Frequency to be defined by organization. Monitoring measures should be relevant to the desired program outcomes | Number of education needs assessments carried out per year | Number of education needs assessments required per year | 100% | NA | New | M&E plans and results | No tool required; INEE MS and indicator definitions sufficient | During program implementation | ||

| Evaluation (FDN/Analysis Std 4) Systematic and impartial evaluations improve education response activities and enhance accountability. |

1.8 Number of evaluations carried out | Number of evaluations carried out | NA | NA | New | M&E plans and results | No tool required; INEE MS and indicator definitions sufficient | Program completion | ||||

| 1.9 Percentage of evaluations shared with parents | Number of evaluations shared with parents | Number of evaluations | 100% | NA | New | M&E plans and results | No tool required; INEE MS and indicator definitions sufficient | Program completion | ||||