Education in Emergencies Essay Contest

The Essay Contest, which was part of the 10th Anniversary Celebration of the INEE Minimum Standards in the latter half of 2014, was intended to share knowledge, increase awareness of education in emergencies, and provide an opportunity for people around the world to share their thoughts and ideas about what education means to them in times of crisis.

The Essay Contest, which was part of the 10th Anniversary Celebration of the INEE Minimum Standards in the latter half of 2014, was intended to share knowledge, increase awareness of education in emergencies, and provide an opportunity for people around the world to share their thoughts and ideas about what education means to them in times of crisis.

INEE received 722 essay submissions in Arabic, English, French, and Spanish from 52 countries around the world! Essays were judged anonymously by age group, across all languages, based on their relevance to the education in emergencies topic, clarity, creativity, innovative thinking, organization, cohesiveness, and impact on the reader.

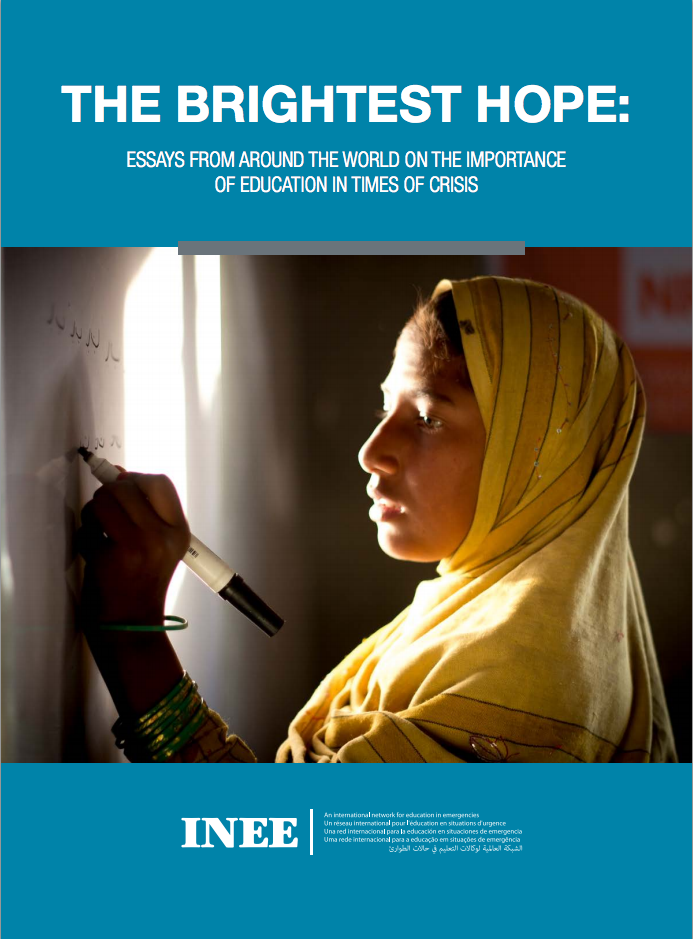

Many essays were incredibly strong, and a select few have been highlighted in a special booklet, The Brightest Hope: Essays from around the world on the importance of education in times of crisis.

In addition to the broader collection of essays in the booklet, the contest resulted in three outstanding winning essays, which are included below. Congratulations to each of the winners! And thank you to all who participated and shared your stories! We would like to acknowledge, with gratitude, WarChild Holland for providing the education related prizes for the winning entries.

Announcing the 2014 INEE Essay Contest Winners!

6-12 years age group

Mehreen Mirza, 12, Bangladesh

Mehreen is in grade 6. Her hobbies include scrapbooking and reading fantasy stories. When she grows up, she wants to work in an organization and write articles to raise awareness on human rights.

Life can be short, life can be long. Life is always valuable. There are some needs without which life’s value is lessened. Needs like education, which is the foundation of a strong future. Being illiterate is like being blind. This is what I felt when my education had been taken away for a short while.

Over the past few years, I had missed some days of school due to political unrest. My learning had been seriously hampered. My school was closed except of a few weekends and my syllabus was incomplete. The seniors communicated online, which my junior class could not do. Without education, I felt restless and disabled.

I would like to tell those in similar situations to quench their thirst for knowledge. When education is taken away, one’s curiosity and thirst for literacy may reach an unbearable stage. I am grateful to those who provide learning in these times.

13-17 years age group

Ayesha Saleem, 14, Pakistan

Ayesha is in grade 9. She loves to read novels, especially horror stories. She enjoys playing games on her laptop, watching TV, studying, making new friends and meeting new people. When she grows up, she wants to be a doctor.

The Luckiest Survivor

I woke up as the sparkling sun rays fell upon my face. It was my first day at school and my excitement was at its peak. Like any other child belonging to a poor family, school held a different kind of an attraction for me. But I wouldn’t have thought that my eagerness was short lived and it was to turn into a tragedy. I dressed up quickly, gobbled up my breakfast and headed for school. I was almost flying towards the school. The fear of falling down was almost nonexistent. What mattered to me was my education, my school. I was one of the first few students to reach the school. After brief introductions, the teacher started the lesson. I took my seat beside my best friend. My teacher asked us to take out our English books. As I turned towards my bag something caught my attention.

I saw an overwhelming stream of water flowing right towards us. I froze. I remembered my father fretting over the recent floods in our province and soon realized what was happening. I couldn’t breathe. I turned around to see my class fellows but they were already gone. My heart thudded inside my chest. The flood had hit my town. As I climbed up a nearby tree, I could see people running for their lives. I started crying when I saw my bag floating away.

I don’t remember who pulled me down and how I ended up in a camp. When I returned to my senses, I tried to find my parents. Everything was gone. As I roamed around the camps, I saw my mother packing the things that the flood was kind enough to leave behind. I ran towards her. She started sobbing and told me that we were leaving town and moving to ‘safer’ areas. I could see my brother curled in a ball where my father was sitting holding his head in his hands.

The journey from the camp to the ‘safe’ area was a blur. I tried my best to block out the sounds of crying and moaning. We reached our relative’s house. As the reality sank in, tears started to run down my cheeks. I knew I was lucky to have made it out alive but my incomplete education left a void inside me. For months, I tried to work as a baby sitter for a rich family who treated me well but my heart used to shrink whenever I saw school-going children.

When my employer offered my mother to pay for my school, I thought it was a joke. It was too good to be true and it went against something I had learned from my past: life is unfair. Today, I consider myself an incredible example of how education moulds our lives. We can easily find millions of children who were not as fortunate as me. I have experienced education in emergency and that’s why I consider myself the luckiest survivor.

18+ years age group

Ivy Kimtai, 21, Kenya

Ivy is pursuing a Bachelor of Arts degree in Theatre Arts and Film Technology. She would like to pursue writing and directing as a career, and is currently writing for her school magazine. Her hobbies include reading and writing, watching movies and listening to music, as well as travelling and sightseeing.

Ever since I was a little girl, I knew that if I was to be successful in life, I had to go to school. I come from a small village in Kenya in the Mount Elgon region. I knew that to drive a car, I had to go to school because I was told that anyone who came driving to the village had gone to school. I wanted to come back to the village driving one day and have little children lining up at the side of the road watching and cheering me on, then I would give them candy. In my own little way, education mattered to me.

I attended an academy in Mount Elgon for my Certificate in Primary Education. When I was in standard eight which was the final year in primary education, Mount Elgon region suffered a civic and political unrest. I was lucky to be in a boarding school for my friends who were day scholars would sometimes not attend school because of the insecurity and the fear that had gripped the region.

Rebel forces known as Sabaot Land Defence Forces (S.L.D.F) terrorized Mount Elgon. Their main reason for attack was issues dealing with land. They were merciless; they spared no life, not even animals. They were ruthless in their tactics; they chopped off people’s ears, amputated peoples legs, it was a menace. I remember hearing the hushed voices of teachers in the staffroom talking about how bad the situation was. I heard about how one of them had watched his family from a bush being slaughtered and he couldn’t do anything about it. I remember hearing him weep about how helpless he felt. School was the only safe place because we had the Kenyan soldiers surrounding the place.

Children stopped coming to school. My best friend missed school for close to a week. I was worried sick. He was the only one who could tell me how my family was. I was worried for him and for his family and for my village. The exams were drawing close. Most teachers now lived in school and since most of the standard eight students were boarders we kept on going with our revision for the exams.

Teachers told us that life had to go on, that we had even the more reason to study; education would be our only way out. Amidst gunshots, watching huts rising up in flames in the nearby village, we toiled. We cried for our families’ lives in prayer every night which we happened to spend under the beds. We were living in fear; constant hooting of owls, the gunshots were worse and louder at night. Since we could not go outside to the latrine, we had a bucket in the dormitories, the smell was way better than the smell of death and fresh blood that blanketed the night air.

One of the darkest days of those days is when we heard about the death of our Kiswahili teacher. The school was tense. He was a good man. I remember it was a Friday. We raised the flag in a somber mood and sang the National Anthem. We had heard of his passing as a rumour, we waited for confirmation from the school head, hoping that that was all it was, a rumour. His family had been attacked the previous night and since the rebel group always looked for the man of the house, he was hiding in the ceiling; he was found and shot dead as his wife and children watched. We sobbed in silence.

Education had saved our lives. If it were not for being in school, most of us would have lost our lives, or worse still, we would have become child soldiers. Education was the only way out of this menace. We had to let the region know that there were better ways of solving conflicts than war. We would teach the region that land is not the only asset you can have.

The lights in the dormitory had to be switched off at night so as to attract less attention to us, except for the security lights outside. Every night until the wee hours of the morning together with the rest of the students, we crammed at the window, reading with the dim lights. You were lucky if your bed was close to a window. You even got more friends. More favours. More bread during tea break the following day.

Being in school guaranteed us food and water. Food was a scarce commodity during that period. Mount Elgon is an area that has fertile soils therefore most of our food produce is in the farms. The rebels burnt most of that down to paralyze the village. The only food was dry maize which needed to be taken to the Posho mill to be ground but they were all shut down because of insecurity reasons. All shops were closed if not looted by the rebels hence food scarcity, unlike the entire village, we still could have three meals a day and drink clean water.

Most of the young girls had been raped and left mentally scarred, wounds that in more cases than none are almost incurable. Many women and young girls were molested and either infected with HIV and or got pregnant. Those of us in school, education had allowed us the sanity of our innocence.

I remember when the results came out, that was the year our school had performed the best in its history. The government had somehow managed to contain the situation. Most of us had passed and went to prestigious national schools. I went to a national school.

I remember all this like it was yesterday. I am now in my final year in University. Education got me here. Until I can buy a car, drive back to my village; have children lining up by the side of the road and giving them candy, I am not there yet.