Out of School, Out of Sight

On July 15th, UNESCO Institute of Statistics and the GEM Report organized a side event, moderated by INEE, at the High-level Political Forum (HLPF) in New York entitled: “Out-of-school, out of sight? How to reach millions of children and youth denied education opportunities, including in emergency and crisis contexts”. The keynote address of this event was given by Karen AbuZayd, Special Adviser of the UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants.

Ms. AbuZayd’s address is fact-filled and touching, and we are pleased to share the full transcript of it with you. You can also watch a recording of this keynote address and other segments of the event on UNESCO’s YouTube channel. Ms. AbuZayd’s speech is from 27:28-38:40. The full event video runs 1h28m.

Karen AbuZayd’s keynote address in full:

I would like to thank UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics and the Global Education Monitoring Report for their profound work in compiling the evidence base to show us the progress thus far toward the goal of free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education. Your report offers a great deal of encouragement: over the past 15 years, the percentage of children in school has increased, and gender disparities have been reduced. Overall, better policies and investment are having an impact.

I would like to thank UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics and the Global Education Monitoring Report for their profound work in compiling the evidence base to show us the progress thus far toward the goal of free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education. Your report offers a great deal of encouragement: over the past 15 years, the percentage of children in school has increased, and gender disparities have been reduced. Overall, better policies and investment are having an impact.

While these broader trends are positive, and deserve to be celebrated, they do not tell the whole story. Many children are still being left behind when it comes to education, and today I am grateful for the opportunity to speak with you about forcibly displaced children, a group of children whose rights to education have yet to be realized.The title of this session refers to an ‘education crisis’ for this group, and that is not an exaggeration.

Since this is an event specifically about data, we should start with the numbers, which – I will warn you – are not exhibiting the positive trends that we see in the broader report on universal education.

- According to the most recent estimates by UNHCR, there are 21.3 million refugees (16.1 million under UNHCR mandate and 5.2 million registered by UNRWA) and 40.8 million internally displaced persons. More than half of refugees are under the age of 18. That fact should stay in our minds as we speak about education. Education can’t be marginal issue when the majority of refugees are children.

- The duration of displacement exceeds in many cases the length of an average basic education cycle. To take a contemporary example, the Syrian civil war has already lasted more than a full primary education cycle in the country. Most protracted refugee situations last longer than 20 years. That is a generation.

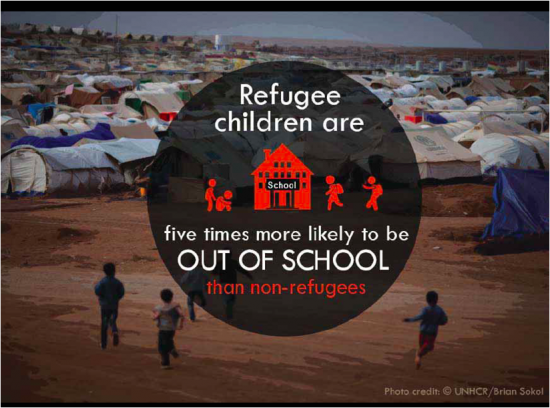

- Refugees are five times more likely to be out-of-school than their non-refugee peers. Half of the world’s refugee children are still missing out on primary education, and three out of four have no access to secondary education.

We often hear talk about the current refugee numbers being a ‘crisis’ and that the numbers of forcibly displaced are higher than at any time since the Second World War. This framing of the issue can cause people to feel overwhelmed and fearful. At the time of WWII, the population was roughly a third of what it is today, and war had devastated vast territories, populations and economies.

Surely what we are facing now is not a crisis of numbers, but one of international solidarity.

In the area of education, this lack of solidarity is seen clearly in the data on funding. In a nutshell, funding for education of refugee children is scarce. Development aid is by far the biggest source of support, but countries affected by crises often receive less aid, not more. For example, in 2013, development aid per primary school-aged child was on average US$15 per child in countries not in protracted crises, but US$7 per child in 17 of these countries in protracted crises. That is, countries in crisis received less than half the amount of aid per capita as similar countries that did not have a crisis. I suppose there are reasonable explanations for this, such as the capacity of the state to absorb the development aid, but the impact on children is seen in the low enrolment rates and, undoubtedly, the quality of education.

Humanitarian appeals cannot fill the gap. They generally include only a small provision for education: in 2013 only 2% of funds from humanitarian appeals were directed to education. Even these modest appeals are critically underfunded. So far this year, global humanitarian appeals for education funding have received only 24% of the funds requested.

It was because of the imperative to mobilize international solidarity that the General Assembly decided to convene the ‘UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants’ on 19 September. The Secretary-General set forth his vision for the Summit in a report issued in early May. This report puts education at the heart of our solidarity with refugees. Let me say a few words about why that should be the case.

First, education is the right of every child. States have pledged in the 2030 Agenda to ‘leave no one behind’ and to help those furthest behind first. Refugee children surely fall into the group of ‘furthest behind.’

Second, the Secretary-General’s report talks about education being ‘fundamentally protective’ in the context of displacement. Education restores a natural rhythm to the days of refugee children; it gives them a sense of normalcy amid the chaos that has overtaken their young lives. It gives them a place of safety, order and expression. Education also protects families by reducing the stress and worry of parents.

Finally, education of refugee children has benefits that extend beyond the children themselves. Refugee children are the future of their war-torn countries. If they return home with education, their knowledge and skills will enable them rebuild their lives and their communities. The future of peace and reconstruction will depend on these children. It is foolish, short-term thinking not to invest in them.

In recent months, there has been greater attention to the education of refugee children. At the World Humanitarian Summit, the Education Crisis Platform was launched in an effort to provide faster and flexible support for education. There are also efforts underway to create specific funds for scaling up refugee children’s access to education, as in the “Education Cannot Wait” initiative.

The political declaration of the UN Summit is currently being negotiated. I am pleased that the current draft has strong language on education. It includes a commitment to providing quality primary and secondary education for all refugee children ‘and to do so within a few months of the initial displacement.’ If adopted, this would demonstrate a broad political will at the highest levels toward the education of refugee children.

The collection and analysis of data about refugee children’s education will play a critical role in holding us all accountable for achieving this goal. We must have a reliable evidence base to show us which refugee boys and girls are out of school, at which grade levels, and where. This will help us target a more substantial pool of funds to areas where it will have the greatest impact. It will help us to measure progress over time. In a few years’ time, we want to see that the number of refugee children out of school has decreased substantially, as we can see in the trends for the broader population. Then it will be time to celebrate international solidarity, rather than to bemoan its weakness.

We have focused today on the numbers rather than the children themselves. If they were in the room with us, I try to imagine what they would say. Having worked for over thirty years with refugee families, I recall thousands of refugee children and youth that I have heard over this career. In almost every one of my encounters with refugees, education was a theme. Children would tell me how much they missed going to school. They would tell me about dreams of becoming a teacher, engineer or doctor, which would break my heart since as an adult I realized that their circumstances would not afford them the opportunity to realize those dreams.

Then there are the stories of academic success against all odds. In my experience, refugees place a particular value on education, since it is often the only thing they can carry with them. When education is offered, they take advantage of it with inspiring enthusiasm. I recall refugees sharing books under the shade of trees; taking exams and excelling in them, despite sweltering conditions; and applying proudly for scholarships to college.

If we can give refugees hope for education—by demonstrating political will, mobilizing resources and holding ourselves accountable through an evidence base of solid data—then refugees will repay this investment. In that I have every confidence.

The views expressed in this blog are the author's own.